Environment & Planning – Significant trees: when will damage to a dwelling justify removal?

A recent decision of the ERD Court has provided some clarity on the circumstances which may justify the removal of a significant tree, particularly with regard to ‘unacceptable risk’ and ‘substantial damage’. The decision also reinforces the fundamental duties that experts owe to the court in giving evidence on matters within their field of expertise. The decision is available here.

Background

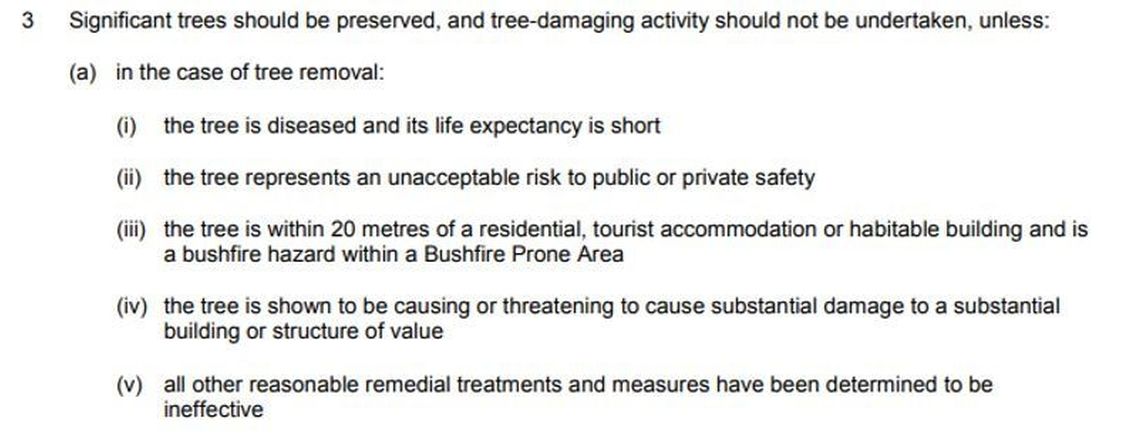

The appellant sought the removal of a significant River Red Gum located in her backyard, approximately 16 metres from the closest part of her dwelling. The Council refused the application on the basis that the tree did not satisfy any of the criteria of the following principle in its Development Plan:

Central to the appellant’s case was her claims that the tree presented an unacceptable risk to private and public safety as well as causing significant structural damage to her dwelling.

Unacceptable risk to safety

There was an obvious disconnect between much of the lay evidence from the appellant and her current and former neighbours and the evidence of the Council’s expert arborist in relation to the risk to public and private safety posed by the tree.

The appellants expressed deep concerns and fears for their safety, which were cited as the central reason for her ceasing occupation of the dwelling. Combined, the lay witnesses viewed the tree’s potential to drop limbs at any given time to be an unacceptable risk to safety which warranted the tree’s removal.

These concerns were not shared by Mr Lodge, the Council’s expert. While it was generally accepted that limb drop in River Red Gums are somewhat unpredictable and can occur even in healthy specimens unrelated to weather or stress, the risk analysis performed confirmed that there was a low probability of limb failure. This was consistent with a lack of any evidence suggesting regular limb failure in the past, and a lack of any diagnostic features suggesting that the tree was in declining health.

In accepting the assessment of the expert, the Court also relied upon the observations of Judge Cole in Cheun v City of Onkaparinga [2004] SAERDC 21 where she stated:

the Development Plan seeks to preserve trees of more than a specified size in the urban environment. A degree of risk is implicitly accepted

and ultimately was unable to find on the evidence before it that the tree posed an unacceptable risk to public or private safety.

Structural damage attributable to the tree

There were conflicting views between the expert structural engineers as to the amount of damage to the dwelling that was attributable to the tree. It was not in dispute that the dwelling had suffered substantial structural damage and that the causes of that included suspected inadequate strip footings in conjunction with extremely reactive soil.

Both of the engineering experts agreed that the tree had made some contribution to the extent of damage to the dwelling, but disputed the extent. The Council’s expert, Mr John, suggested that the tree was only a minor contributor and that the dwelling would have suffered the same or similar damage even if the tree was not in the backyard and that the signs and location of cracks in the dwelling were not consistent with the tree being the cause.

This contrasted with the opinion of the structural engineer engaged by the appellant who estimated a 60% apportionment of the damage as being caused by the tree.

The opinion of Mr John was preferred by the Court and aligned with the observations that were made by the Commissioner at the site inspection.

Reasonable remedial options

Again, there was a divergence of opinion on the reasonableness of remedial measures from the witnesses called, particularly in relation to the installation of a root barrier.

Both of the experts engaged by the Council were of the view that a root barrier would have been an effective solution to any damage that could have been attributable to the tree and would be a proportional response as it would have “the same effect on the building as removal of the tree”.

In the view of the appellant’s experts, the installation of a root barrier would be potentially ineffective in mitigating further damage and would not have been a reasonable solution compared to simply removing the tree, based upon the extent of the root network as well as the cost.

The Council’s experts were again preferred with the Court finding:

While the recommended soil moisture monitoring and installation of a root barrier will be neither a quick nor inexpensive undertaking, (circa $15,000-$35,000 depending on the depth to which the barrier needs to be constructed and the excavation methodology adopted) it will likely be far less expensive than the balance of the recommended remedial measures which need to be carried out in order to repair the building and render it less susceptible to ongoing structural damage.

For these reasons, I am unable to say that the root barrier is an unreasonable or an ineffective remedial measure.

Role of the expert in giving evidence

One important takeaway from this decision is the proper role of an expert in giving evidence on matters that are within their field of knowledge, a point the Court made when considering the evidence given by the Appellant’s engineer. An expert who is called to give evidence of opinion on technical matters must always be aware that their chief responsibility is to aid the Court’s assessment of the evidence, and not to further the case of the party who called them, or to be influenced by a desire to minimise exposure to professional indemnity. To stray outside matters of which the expert has direct knowledge is to misunderstand the role with which they are tasked.

Costs

Whilst the usual position is that parties bear their own costs in appeals on the planning merits, the appellant sought costs on the basis that delays in the assessment of the application had allegedly caused lost rental opportunity. The Council opposed the order and the Court confirmed the view expressed in Hutchings v District Council of Lacepede (No 2) [1998] SAERDC 528. that the Court simply does not have the power to order costs in these matters, even if the circumstances supported this.

For more specific information on any of the material contained in this article please contact Aden Miegel on +61 8 8217 1342 or AMiegel@normans.com.au.